The Bayreuth Rings – A Review

The Bayreuth Rings between Barenboim and Janowski: Levine’s Götterdämmerung and Thielemann’s Walküre

The Bayreuth Ring videos on Opera on Video

Here is my review on the existing videos from the Ring productions between 1994 and 2010 at Bayreuth: the 1997 Götterdämmerung conducted by James Levine, and the amazing 2010 Walküre under Christian Thielemann’s magic baton.

Between 1992 and 2016, there were three productions of the Ring at the Bayreuth Festival, which weren’t filmed completely. Three productions, the first one between 1994 and 1998 directed by Alfred Kirchner and conducted by James Levine, the second one between 2000 and 2004 by Jürgen Flimm, conducted in its first year by Giuseppe Sinopoli and the remaining ones by Adam Fischer, because of Sinopoli’s death, and between 2006 and 2010 by Tankred Dorst and conducted by Christian Thielemann. As the Ring, as well as Parsifal, is the icing of the cake for every Bayreuth season, every staging has its complicated working progress and setting, as well as it should offer a new, interesting vision.

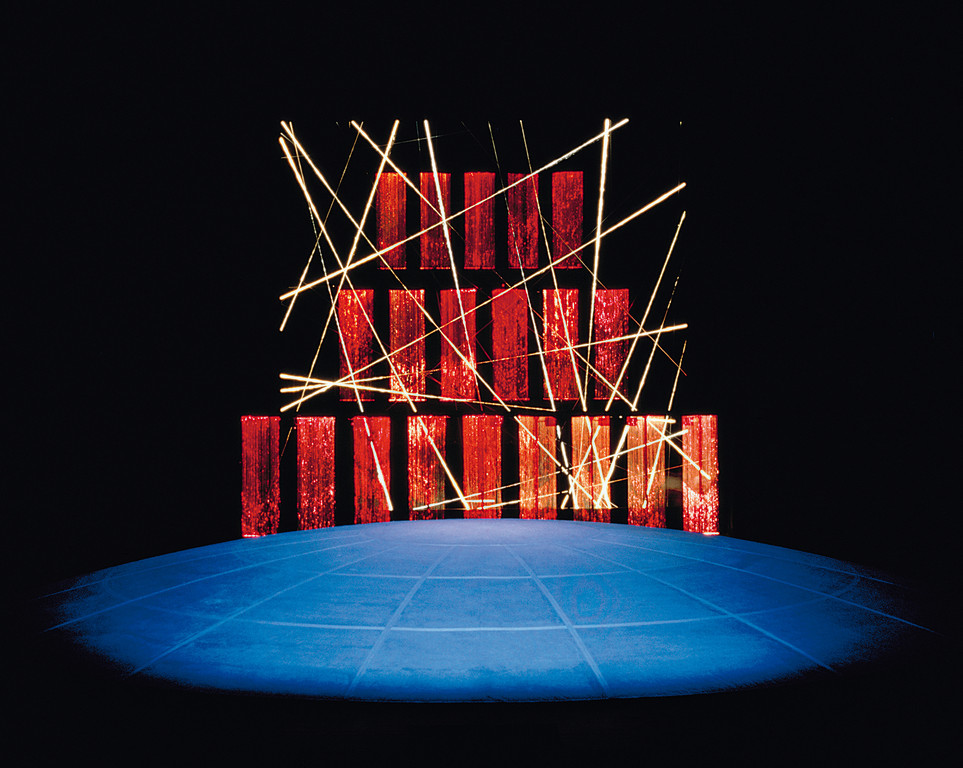

The 1994-1998 Ring directed by Alfred Kirchner became known as the “designer’s Ring”, because of the plastic artist Rosalie’s sets and costumes. Only Götterdämemrung was filmed in 1997, without audience. However, the documentary of the following year ‘The Road to Bayreuth’ shows some fragments of the entire cycle. It seems a very minimalist, simple Ring, which does not dwell on ideologies or brainy reflections, but tries to do more with less: it tries to be spectacular with the few, but spectacular resources that Rosalie displays on stage. Rosalie and Kirchner show enormous infrastructures that appear to be simple, but the documentary reveals to be done through a complicated process. The problem is that such minimalist beauty can also be boring. Even if there is a clear influence or similarity to Wieland Wagner’s ‘New Bayreuth’ stagings. One recognises on stage the drama that the music is telling us, but the feeling of déjà vu and boredom are present. And it doesn’t seem to please much people: ugly for those who want a more traditional option, and boring and classical for lovers of thought-provoking stagings. And one thing that is a problem is the costumes, large, colourful, with armour and enormous hips, or backpacks like those of Alberich or gigantic masks more similar to the Lion King musical that the giants wear on their backs… a costume more typical of cartoons such as Disney’s, or the Transformers, or B Sci-fi fiction or a than of a staging worthy of the Festival.

In the documentary, we see excerpts from Rheingold, where a huge screen of blue lights recreating waves dominates the stage, with a round floor, the stage around which the whole cycle takes place, illuminated in blue, and in the centre a huge structure of three wings on which the Daughters of the Rhine play, and in the centre of it an illuminated triangle, which is the Gold. In 1994, the costumes of the Daughters of the Rhine were longer than in 1998. There are also fragments of the finale, showing how they make a rainbow infrastructure with tubes of rows of cubes with lights inside them, and in the background a formless structure of huge poles that are the Walhalla. From Die Walküre, we have the beautiful duet of the gods, again with the huge screen of glowing lights, now sky-blue, and a huge ramp down which the gods walk. We can also see the highlights of the third act: the ride of the Valkyries, in which the Valkyries dance on high, attached to platforms that move constantly throughout the scene. From the finale, we see that the screen of blue lights is now bright red, and Brünnhilde sleeps surrounded by a Magic Fire circle made of bright police siren lights. From Siegfried we only see the Murmurs of the Forest, in one of the most successful moments of the cycle: a sea of green umbrellas recreating the forest and their breeze.

In these excerpts John Tomlinson can be heard, singing a beautiful ‘Abendlich strahlt der sonne auge’, much better than in Barenboim’s complete Ring, as well as Richard Brunner in a wonderful Froh a little earlier. In the Act II excerpt from Walküre, Tomlinson is heard again, with Hanna Schwarz as Fricka in a state of grace, even more spectacular in voice than in her legendary recording of Boulez’s Ring two decades ago. In the forest murmurs is Wolfgang Schmidt, who sounds best in the first few phrases, with a vigorous, even tender voice, soon to deceive deeply, by making us listen his unpleasant, vociferous vocal timbre in ‘Meine mutter, ein Menschen weib!’

As for Götterdämmerung, once again, Wieland’s influence is visible in the second act, reminiscent of his famous 1956 staging. The curtain opens with the spherical stage empty, while the Norns wander about on it, in beekeepers’ costumes, with huge arms that fold to shrink. In the background, Loge’s red light. In the scene of Siegfried and Brünnhilde, again the rock of the Valkyries represented by a wing-shaped structure that looks like a ship’s sail. Brünnhilde wears a rare blue shield with a blue coat of arms that emphasises her breasts. Siegfried, in a pair of trousers with a matching light blue waistcoat, with a boyish attitude rarely seen. The Gibichung’s palace is represented by containers suspended in the air, and a pair of thrones on which Gunther and Gutrune sit, the latter resembling a peephole. In Rosalie’s words, she is nothing more than an object of exhibition. The most successful part of this staging is the second act, where there is hardly any infrastructure. Hagen, static, appears in absolute emptiness while Alberich walks around him. Then in the second scene, the chorus sets up their spears and surrounds the protagonists, in a nod to Wieland’s staging as already mentioned. The third act begins with poles planted, and the stage illuminated in green, and blue, the latter half being where the Daughters of the Rhine move, both dressed in a tyical nineties’s aesthetics, with coloured bows. The finale is a play on light, but equally exciting: the huge screen of lights appears first incandescent red, then blue. The Rhine daughters drag Hagen to the back of the stage and then themselves. A massive pole structure appears in the background, which is Walhalla burning in deep red light. Finally the stage appears empty, with the floor all blue: the waters of the Rhine have returned to their course, and the curtain falls.

James Levine conducts a very powerful Bayreuth Orchestra, with slow tempi, typical of his conducting, but as Thielemann would later do, by using slow tempi that alongside the spectacular sound of the orchestra, giving the performance an epic, solemn, tragic dimension.The strings penetrate the ear, shining brightly, the sound of the clarinet in the first act interlude reminded me very much of what I heard in the Tannhäuser performance I attended last August there,, which makes me wonder how far the sound engineering faithfully reconstructs the acoustics, including the spectacular percussion and brass. The same goes for the chorus: the same chorus that seems to eat up the orchestra as it dialogues with Hagen is able to deliver an incredible pianissimo in ‘Heil dir, Gunther’.

At that time, Deborah Polaski was an important Brünnhilde. The American soprano is at her best, with a spectacular voice, and despite her perhaps slightly dull tone in later years, here the high voice is firm and the sound of the voice quite remarkable. As an actress she is excellent, showing a fragility and bewilderment like few others, in the scene where she enters with Gunther at his wedding. Eric Halfvarson is the other star of the cast, with his dark, well-sung Hagen, which I saw him in at the Royal six years later. As an actor he is even more interesting, with his pale characterisation, and showing a more human Hagen, with a more fragile side, as opposed to the brute we are used to imagine.

The same cannot be said of Wolfgang Schmidt as Siegfried. While it must be acknowledged that the voice is big and remains equally strong, it does not have a pleasant sound. His singing is vociferous, yelling, especially at the highest voice. There is no beauty, only screaming and tough singing.

Falk Struckmann is an excellent, low-voiced and beautifully sung Gunther, and Anne Schwanewilms, at the start of her career, a sweet Gutrune, sung with that peculiar timbre of hers that worked for her fot the following two decades, though it is fair to say there have been better ones in this role. The veteran Hanna Schwarz is a Waltraute with a round, dark, almost contralto voice. The years do not seem to have passed this mezzo who twenty years earlier sang in the Centenary Ring. Ekkehard Wlaschiha is an Alberich whose massive, vociferous voice suits the unpleasant dwarf.

From the Flimm/Sinopoli-Fischer Ring no complete videos exist, but only a documentary showing the rehearsals, showing some clips of what must have been an interesting staging, specially in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, by showing distant landscapes. At the end of Götterdämmerung, a child dressed with Parsifal’s armour is shown in an empty staging, as if showing the way of redemption.

Why did Opus Arte release only the audio of Thielemann’s entire 2008 Bayreuth Ring and not the video of the complete cycle? There are many speculations. One of them is that the staging by Tankred Dorst, who replaced Lars Von Trier at the last minute, did not convince the critics, the artistic guild and, it seems, most of the Bayreuth audiences. It was a staging quite faithful to the Wagnerian myth, judging by the photographs, but with nods to modernity, interspersed in an inconsistent way, according to those who had seen it. Specially, any reason when after seeing this Walküre, filmed in 2010 during a live performance, Siegfried has a first act set in a school, and the rude hero splits in two not an anvil but a globe, or that the Gibichungs scenes are a carbon copy of Patrice Chéreau’s staging. Another reason could be that if this was a traditional, but unsubstantial staging, and the only reason to preserve it was Thielemann’s baton, this Ring would have too much competition in the market. To preserve Thielemann’s performance, there would be enough with the audio. However, having completed four of the last seven productions of the Bayreuth Ring, and leaving aside the two unbeatable productions by Chéreau and Kupfer, this one by Dorst, had it been released in its entirety, could have been an alternative to Castorf’s showy and ultra-modern one, and by far better than Schwarz’s tedious and soap-operatic one.

Dorst, in an attempt to please everyone, with so little time to prepare the staging and not much opera experience, makes a Valkyrie that in my opinion is beautiful, but that remains just that. And there are intersections of the modern that are not explained. Thus, the first act takes place in a ruined mansion, hit by an electric pole that has fallen on it. A group of people (possibly refugees, as Germany was receiving in those years) flee the place with their suitcases, while a boy lifts a woman’s veil, and runs away: it is Sieglinde, who looks dishevelled. Siegmund enters and she, in early 19th century clothes, offers him water. Hunding enters with his entourage, wearing animal masks. Hunding appears dressed as a Prussian or Austro-Hungarian military man. This setting is another nod to Chéreau’s.

The second act begins spectacularly: Wotan and Brünnhilde, dressed in costumes taken from the Star Wars trilogy directed by George Lucas in those years, appear on a rock, overlooking the cloud-covered landscape. These clouds give way to a collection of crumbling statues, in a rocky landscape with some green, like the remains of a civilisation in ruins. Two men in ram helmets appear: behind them Fricka enters, wearing a black suit straight out of some cross between Star Wars and a Tibetan monk. When Wotan kills Hunding with a gesture, his henchmen flee.

For the Valkyries’ rock in the third act, an imposing rocky landscape, the structure of which resembles either a cave or a ruined factory. To the left of the stage is the German phrase ‘They love life, we love death’. The Valkyries (dressed like their sister) awaken the heroes fallen in battle. The final scene is a success: Wotan and Brunhild bid each other an emotional farewell, and Wotan weeps after putting his daughter to sleep. Then the tip of Wotan’s spear lights up and the whole stage fills with smoke and an orange light takes over the scene, creating a spectacular sight to behold, with the curtain falling.

Christian Thielemann‘s orchestral conducting is spectacular, in contrast to his not very impressing one Berlin of two years ago: with the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra he is like a duck to water, and both achieve a result that might qualify as the best modern Walküre on video, and among the best ones. From the prelude onwards, the orchestra sounds authoritative, with those powerful strings evoking the storm. The wind, with an imposing sound. The cello, creating a cosy feeling in the first scene. The Prelude to Act II and the Ride of the Valkyries exalt the Wagnerian emotions, with a spectacular rendition. Thielemann’s tempi are usually slow, but his solemn, grandiloquent style is of the highest level. Once again, thrilling Magic Fire… how beautiful this music is and how well it sounds in Thielemann’s baton.

Johan Botha is a Siegmund with a lyrical, beautifullly sung, youthfully-toned, and at the same time vigorous voice, despite some problematic high voice. Undoubtedly, he is the best of a cast that sounded wonderful despite not being among the best of the time. Edith Haller, whom I remember as a great Elisabeth in Tannhäuser in Madrid in 2009, is a Sieglinde with a powerful voice, dramatic timbre, and though she can sound musically monolithic, I find her solemn and tragic for this character living her own tragedy. Kwangchul Youn is an excellent Hunding.

Albert Dohmen is a good Wotan, here at his best, although his voice is beautiful, though not very deep, but sometimes nasal, especially on the u and o vowels, including those with umlauts, which he pronounces gutturally. Still, in the third act he shows his worth as an actor, portraying a furious but at the same time fragile Wotan, and as a singer giving a beautiful version of the final monologue. I have to say that I have to reconsider what I think of Linda Watson: I always found her voice very high-pitched and very dull. But even so, in this video she doesn’t sing badly at all and her commitment to the staging and the role is evident, even if physically she looks more like Wotan’s wife than his daughter. Mihoko Fujimura is a fine Fricka: not a powerful voice, but with a deep and commanding sound, unlike some of today’s mezzos who are rather light. The eight Valkyries are excellent.

The performance ends with an enthusiastic reception by the audience, especially a Thielemann in a state of grace that is not at this level in other recordings of the Ring outside Bayreuth. It is a pity that this Ring is not preserved in its entirety, as there is only one traditional video version, Levine’s from the 90s Met. But discography, alas, is also a business and depends on sales. The same could be said of the interesting minimalistic Ring of Levine/Kirchner, but it couldn’t compete with the Boulez’s and Barenboim’s previous ones. Not even the aforementioned Levine Ring from the Met.

Let’s hope streaming could help us to preserve the Bayreuth stagings to come in the next decades, as for every Wagnerian, every Bayreuth staging is an interesting world to delve.

Angel Parsifal